These are the backbone of any accounting system. Understand how debits and credits work and you'll understand the whole system. Every accounting entry in the general ledger contains both a debit and a credit. Further, all debits must equal all credits. If they don't, the entry is out of balance. That's not good. Out-of-balance entries throw your balance sheet out of balance.

Debits and Credits vs. Account Types

Account Type Debit Credit

Assets Increases Decreases

Liabilities Decreases Increases

Income Decreases Increases

Expenses Increases Decreases

Notice that for every increase in one account, there is an opposite (and equal) decrease in another. That's what keeps the entry in balance. Also notice that debits always go on the left and credits on the right.

Let's take a look at two sample entries and try out these debits and credits:

In the first stage of the example we'll record a credit sale:

Accounts Receivable $1,000

Sales Income $1,000

If you looked at the general ledger right now, you would see that receivables had a balance of $1,000 and income also had a balance of $1,000.

Now we'll record the collection of the receivable:

Cash $1,000

Accounts Receivable $1,000

Notice how both parts of each entry balance? See how in the end, the receivables balance is back to zero? That's as it should be once the balance is paid. The net result is the same as if we conducted the whole transaction in cash:

Cash $1,000

Sales Income $1,000

Of course, there would probably be a period of time between the recording of the receivable and its collection.

That's it. Accounting doesn't really get much harder. Everything else is just a variation on the same theme. Make sure you understand debits and credits and how they increase and decrease each type of account.

Assets and Liabilities

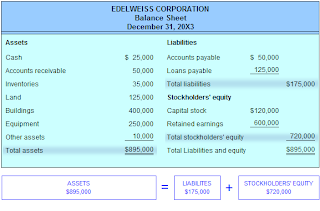

Balance sheet accounts are the assets and liabilities. When we set up your chart of accounts, there will be separate sections and numbering schemes for the assets and liabilities that make up the balance sheet.

A quick reminder: Increase assets with a debit and decrease them with a credit. Increase liabilities with a credit and decrease them with a debit.

Identifying assets

Simply stated, assets are those things of value that your company owns. The cash in your bank account is an asset. So is the company car you drive. Assets are the objects, rights and claims owned by and having value for the firm.

Since your company has a right to the future collection of money, accounts receivable are an asset-probably a major asset, at that. The machinery on your production floor is also an asset. If your firm owns real estate or other tangible property, those are considered assets as well. If you were a bank, the loans you make would be considered assets since they represent a right of future collection.

There may also be intangible assets owned by your company. Patents, the exclusive right to use a trademark, and goodwill from the acquisition of another company are such intangible assets. Their value can be somewhat hazy.

Generally, the value of intangible assets is whatever both parties agree to when the assets are created. In the case of a patent, the value is often linked to its development costs. Goodwill is often the difference between the purchase price of a company and the value of the assets acquired (net of accumulated depreciation).

Identifying liabilities

Think of liabilities as the opposite of assets. These are the obligations of one company to another. Accounts payable are liabilities, since they represent your company's future duty to pay a vendor. So is the loan you took from your bank. If you were a bank, your customer's deposits would be a liability, since they represent future claims against the bank.

We segregate liabilities into short-term and long-term categories on the balance sheet. This division is nothing more than separating those liabilities scheduled for payment within the next accounting period (usually the next twelve months) from those not to be paid until later. We often separate debt like this. It gives readers a clearer picture of how much the company owes and when.

Owners' equity

After the liability section in both the chart of accounts and the balance sheet comes owners' equity. This is the difference between assets and liabilities. Hopefully, it's positive-assets exceed liabilities and we have a positive owners' equity. In this section we'll put in things like

Partners' capital accounts

Stock

Retained earnings

Another quick reminder: Owners' equity is increased and decreased just like a liability:

Debits decrease

Credits increase

Most automated accounting systems require identification of the retained earnings account. Many of them will beep at you if you don't do so.

By the way, retained earnings are the accumulated profits from prior years. At the end of one accounting year, all the income and expense accounts are netted against one another, and a single number (profit or loss for the year) is moved into the retained earnings account. This is what belongs to the company's owners-that's why it's in the owners' equity section. The income and expense accounts go to zero. That's how we're able to begin the new year with a clean slate against which to track income and expense.

The balance sheet, on the other hand, does not get zeroed out at year-end. The balance in each asset, liability, and owners' equity account rolls into the next year. So the ending balance of one year becomes the beginning balance of the next.

Think of the balance sheet as today's snapshot of the assets and liabilities the company has acquired since the first day of business. The income statement, in contrast, is a summation of the income and expenses from the first day of this accounting period (probably from the beginning of this fiscal year).

Income and Expenses

Further down in the chart of accounts (usually after the owners' equity section) come the income and expense accounts. Most companies want to keep track of just where they get income and where it goes, and these accounts tell you.

A final reminder: For income accounts, use credits to increase them and debits to decrease them. For expense accounts, use debits to increase them and credits to decrease them.

Income accounts

If you have several lines of business, you'll probably want to establish an income account for each. In that way, you can identify exactly where your income is coming from. Adding them together yields total revenue.

Typical income accounts would be

Sales revenue from product A

Sales revenue from product B (and so on for each product you want to track)

Interest income

Income from sale of assets

Consulting income

Most companies have only a few income accounts. That's really the way you want it. Too many accounts are a burden for the accounting department and probably don't tell management what it wants to know. Nevertheless, if there's a source of income you want to track, create an account for it in the chart of accounts and use it.

Expense accounts

Most companies have a separate account for each type of expense they incur. Your company probably incurs pretty much the same expenses month after month, so once they are established, the expense accounts won't vary much from month to month. Typical expense accounts include

Salaries and wages

Telephone

Electric utilities

Repairs

Maintenance

Depreciation

Amortization

Interest

Rent